Anastasia Rydlevskaya:

Zrozumiałam, że czas wyjechać

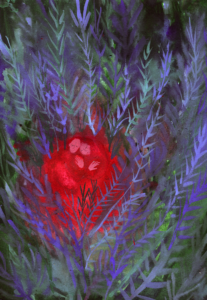

Kolorowe tygrysy, wielogłowe krokodyle, ptaki z ludzkimi twarzami, płaczące kwiaty, haftowane księżyce. Artystka Anastasia Rydlevskaya na prace przelewa wszystkie swoje obawy i lęki, ale też nadzieje. W swoim kraju – Białorusi – tworzyła sztukę zaangażowaną. Kiedy poczuła niemoc, strach o swoją przyszłość i zrozumiała, że na płótnach nie może pokazać tego, co czuje, zdecydowała się wyjechać z tą myślą, że być może nigdy nie będzie jej dane wrócić. W listopadzie 2021 roku przeniosła się do Polski, do Gdańska, gdzie intensywnie tworzy. 11 czerwca w krakowskiej Galerii BB zostanie otwarta jej wystawa „What are you afraid of?”

Colorful tigers, multi-headed crocodiles, birds with human faces, crying flowers, embroidered moons. Artist Anastasia Rydlevskaya pours every last one of her worries and fears into her work. But there’s also hope. In her country of Belarus she created socially engaged artworks, yet when she felt powerless and anxious about her future, when she understood that her canvasses aren’t allowed to represent her true experiences, she decided to leave, and the thought that she might not be allowed to come back became her constant companion. In November 2021 Rydlevskaya moved to Gdańsk, Poland, where she lives submerged in her creative practice. Starting on June 11th you’ll be able to see her newest exhibition, What are you afraid of? in Cracow’s Galeria BB.

Gdzie mieszkałaś przed przeprowadzką do Polski?

Pochodzę z Białorusi, dorastałam w Mińsku, ale w dzieciństwie, przez parę lat, mieszkałam z rodziną w Ameryce. Moi rodzice mieli wizę pracowniczą, ale jak to bywa w Stanach Zjednoczonych, nie zawsze wszystko się układa i ma się szansę tam zostać, więc musieliśmy przenieść się z powrotem.

Czy ktoś z twojej rodziny był artystą?

Nie, ale powiedziałabym, że moja rodzina jest nieco artystyczna. Mama rysuje, tworzy różne ozdobne przedmioty do domu, tata gra na gitarze, a brat jest fotografem.

Co rysowałaś, kiedy byłaś dzieckiem?

Tygrysy, uśmiechnięte koty, nie mam pojęcia dlaczego, ale już wtedy rysowałam kwiaty z twarzami. Rysuję i maluję przez całe życie. Moja mama i tata bardzo mnie wspierali. Kiedy coś rysowałam, tata zawsze mówił: „Och, właśnie stworzyłaś kolejne arcydzieło!” I myślę, że to zdecydowanie pomogło mi w realizacji moich marzeń.

Nie studiowałaś jednak malarstwa.

Planowałam iść na Akademię i intensywnie się do tego przygotowywałam, jednak miesiąc przed egzaminami moi rodzice zaczęli mieć problemy z biznesem i nie byli w stanie opłacić moich studiów. Musiałam wybrać coś, co mogłam studiować za darmo. W ciągu miesiąca po prostu zmieniłam decyzję i zostałam filologiem. Ukończyłam filologię francuską i włoską. Później zaczęłam uczyć literatury na uniwersytecie. Ale jednocześnie nigdy nie przestałam szkolić się w dziedzinie sztuki. Przez dziesięć lat zdobywałam wiedzę z rysunku akademickiego, malarstwa akademickiego, teorii koloru itp.

Where did you live before you moved to Poland?

I’m from Belarus, I grew up in Minsk but I also had a period of my life when I lived in America for a few years. It was about when I was a kid from 2,5 years until 7. My parents had a working visa but you know how it happens in America, you do not always have a chance to stay there so we had to move back to Belarus.

Was anyone in your family an artist?

No, but I would say that my family is very artsy. My mum draws, creates different art objects for her house, my dad plays his favorite songs on a guitar, and my brother is a photographer.

What did you use to draw when you were a kid?

I used to draw tigers, smiling cats, I have no idea why but even then I was drawing flowers and poppies with faces. And I’ve been drawing and painting ever since I remember. My mum and dad were very supportive. When I drew something, my dad was always like: oh you have just created another masterpiece! And I think that it really helped me to just pursue my dreams.

You did not study art though.

I was planning to go to an art academy and I was preparing to go but then one month prior to entry exam my parents had problems with their business and they were not able to pay for my studies, so I needed to choose something I could study for free. In one month, I just changed my whole direction and I ended up being a philologist. I have a bachelor degree in philology in French and Italian languages. After that I started to be a literature teacher at the university that I studied but at the same time I never stopped learning in the art sphere so I have ten years of artistic studies, academic drawing, academic painting, colour theory etc.

Jak pracujesz? Czy masz jakieś przyzwyczajenia?

Obecnie najczęściej tworzę małe grafiki, duże płótna, rzeźby w glinie oraz materiałowe maski. Mam bardzo specyficzną rutynę pracy. Uwielbiam się kąpać. Dosłownie mogę siedzieć cały dzień w wannie, tworzyć nowe prace, a nawet jeść. W Mińsku miałam swoją pracownię w jednym z pokoi w mieszkaniu. I to było fajne, pracowałam i myślałam: „OK, to teraz czas na kąpiel”. Tu w Gdańsku od niedawna mam pracownię na zewnątrz, nie ma tam wanny i zastanawiam się, jak będę pracować!

Moja twórczość jest całym moim życiem. Właściwie pracuję cały czas. Dla mnie to sposób komunikowania się ze światem, który nigdy się nie kończy. Proces twórczy zawsze zaczyna się u mnie od intencji. Potem znajduję sposób na jej wyrażenie na obrazie. Zwykle śpiewam lub słucham muzyki i staram się osiągnąć stan podobny do tego podczas medytacji. Zaczynam odczuwać obrazy. Wyławiam je z nieświadomości i przekładam na jakiś materiał. Nie planuję, co powstanie, nie robię szkiców. Od razu tworzę.

W 2021 zdecydowałaś się opuścić swój kraj. Dlaczego akurat wtedy?

Był 2020 rok. Na Białorusi zaczęły się protesty, braliśmy udział w marszach, walczyliśmy o wolność. Niestety nie wyszło i zaczęły się straszne represje. Żyliśmy w rzeczywistości, w której ludzie byli po prostu zatrzymywani na ulicach, wyciągani z domów i zamykani w więzieniach. Ja byłam artystką zaangażowaną społecznie. Stworzyłam wiele prac protestacyjnych i po prostu zaczęłam bać się o swoją wolność. Po mojej ostatniej wystawie w Mińsku zrozumiałam, że czas wyjechać. Zostawiliśmy z mężem wszystko, co mieliśmy, w Polsce nie czekała na nas praca, po prostu przyjechaliśmy do miejsca, którego nie znaliśmy. Okazało się jednak, że Gdańsk jest piękny, przytulny i bardzo na nas otwarty.

Czy twoi rodzice są nadal na Białorusi?

Tak, moi rodzice nadal tam żyją, mieszkają na wsi. Mają mały domek, ogródek kwiatowy, kury i własną uprawę warzyw. To zawsze było miejsce, w którym nabierałam mocy. Spędzałam tam całe lato. Teraz nie mogę do tego wrócić. Bardzo tęsknię za możliwością przytulenia rodziców.

Jak to było być artystą w swoim kraju?

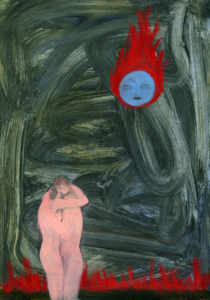

To było naprawdę trudne, bardzo trudne. Moje prace dotyczą przede wszystkim tego, jak komunikuję się ze światem i jak go rozumiem. Tak więc wszystkie moje obrazy pomogły mi lepiej zrozumieć siebie samą i to, o co chodzi w świecie. Na Białorusi żyjesz w dyktaturze, boisz się powiedzieć coś, co może mieć konsekwencje, wyrazić siebie. W 2020 roku wierzyłam, że będziemy wolni. Tak się nie stało. Widziałam tyle bólu wśród ludzi, bliskich, przyjaciół… Moja sztuka zaczęła odzwierciedlać ten ból. To pomagało mi przezwyciężyć traumę. Myślę, że bycie artystą na Białorusi to więcej niż mogę znieść. W tej chwili istnieją tam czarne listy artystów, nie mają już możliwości pokazania swojej sztuki w żadnym miejscu.

Czy w twojej twórczości coś się zmieniło po przeprowadzce do Polski?

Zupełnie zmieniły się kolory. Na Białorusi przez ostatnie dwa lata na moich pracach pojawiało się dużo czerni i czerwieni, dużo „bolesnych” kolorów. Kiedy przyjechałam tu, nieświadomie zaczęłam używać jasnoniebieskiego, różowego, wszystkich tych beztroskich kolorów. To było tak, jakbym zaczęła czuć więcej, jakbym pozwalała sobie czuć więcej. Prace, które tu stworzyłam, są żywsze, jaśniejsze. W swoim kraju czułam się jak w skorupie, byłam odrętwiała przez cierpienie, które było wokół mnie. Tu zaczynam wychodzić z tej powłoki i czuję, że świat jest znacznie większy. I to wszystko widać na moich pracach. Pamiętam, że kiedy przyjechałam do Gdańska, miałam na sobie czerwony szalik z żółtym lwem. Wsiadłam do autobusu i zobaczyłam czerwone siedzenia z żółtymi lwami. I pomyślałam: „O mój Boże, to musi być coś bardzo, bardzo ważnego”. Potem dowiedziałam się, że lew jest symbolem Gdańska i totalnie mnie zahipnotyzował. Te lwy znalazły miejsce na moich pracach – niebieskie, dlatego że są przesiąknięte wszystkimi moimi łzami. Ale pomimo tego uśmiechają się. Patrzę na ich twarze i wiem, że teraz wszystko będzie dobrze, ponieważ jestem tutaj, a lew mnie chroni.

Opowiedz coś więcej o swojej wystawie, która odbędzie się w Krakowie.

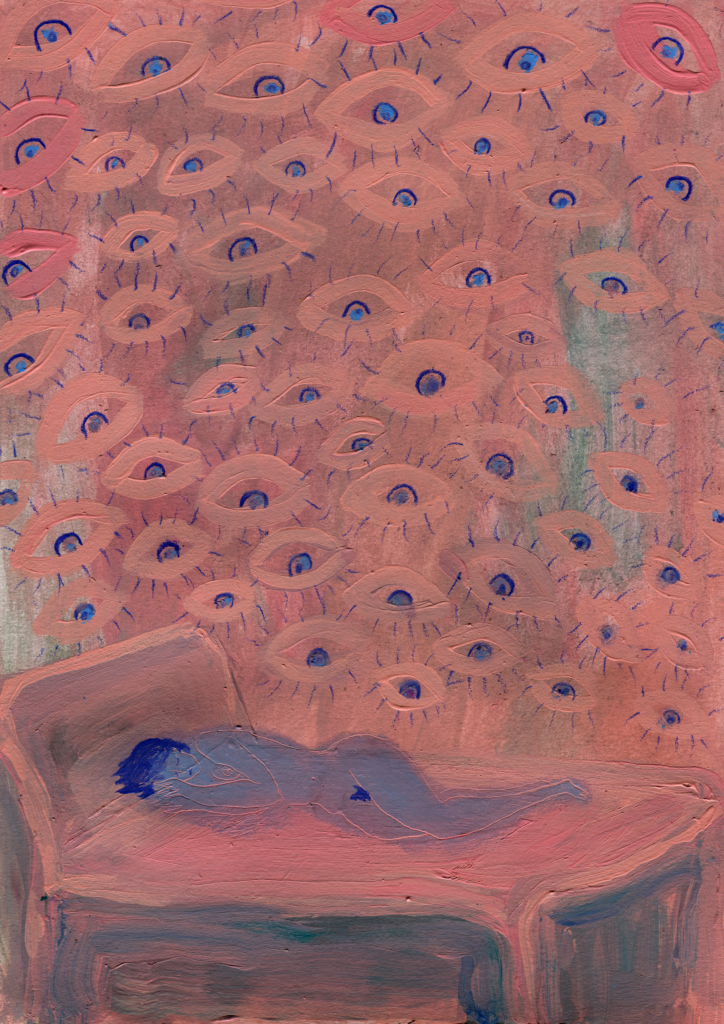

Ta wystawa jest dla mnie bardzo ważna. Wybrane na nią prace dotyczyć będą ostatnich dwóch lat doświadczeń życia w nowej rzeczywistości, nieznośnego stanu, w którym ludzie są zmuszeni funkcjonować. Staram się zrozumieć i pokazać jak się komunikujemy, jak próbujemy wydostać się z przemocy, jak to możliwe by krzywdzić, czy zabić drugiego człowieka. Próbuję w ten sposób znaleźć język do porozumiewania się z tym nowym światem.

Bardzo bliska jest mi myśl Emmanuela Levinasa, francuskiego filozofa, który przeżył Holokaust i próbuje zrozumieć jak żyć w świecie, w którym miała miejsce zagłada, w którym istnieje zło. Podstawowym pojęciem jego filozofii jest pojęcie „innego”. Spotkanie „ja” z „innym”, w którego trakcie buduje się relacja etyczna, polegająca na zapewnieniu drugiej osobie wolności.

Wszystkie moje prace na wystawie zgłębiają temat „niemożności” zabicia drugiego człowieka, tego, że zło istnieje, wojna trwa, ludzie są zabijani i nie możesz z tym nic zrobić, ale z drugiej strony musisz zrobić wszystko, aby to powstrzymać. Przychodzi wiosna, świeci słońce i umierają ludzie. A ty musisz zrobić co w twojej mocy, aby uczynić świat lepszym miejscem, dokonać zmian. Jest coś, dla czego warto żyć. Tym czymś jest samo życie. Miłość.

Co czujesz, gdy kończysz obraz?

Czuję się oświecona. Jakbym trochę więcej zrozumiała o świecie, w którym żyję. I czuję się bezpieczna. To nadaje sens mojemu życiu i mnie.

How do you usually work?

For now, I usually create small graphic works in acrylic and oil pastels, big canvases and small clay sculptures and big masks or other objects with linen.

I have a very specific work routine. I love to take baths. Literally I can stay all day in a bath creating some new paintings, I stay in a bath and I just come up with stuff. I can eat in the bathtub, stay there for six hours and my husband will bring me some food. In Minsk I had a studio in my flat, I had a room for that. And that was cool, I was creating something and I was like: ok that’s my bath time. Here in Gdańsk I have a studio outside and there is no bathtub and I’m trying to make this process work without a bath!

I actually work all the time. My creative life is my life. This is the process I communicate with the world and it never ends. It starts with an intention. After that I find a way to express the intention in images. Usually I either sing, or I create or listen to music and I try to attain a meditative state when I start to feel the images. I catch them out from this unconsciousness that I am in and I create with different material. It’s not something intentional, I do not make sketches. I create right away.

In 2021 you decided to leave your country. Why then?

2020 happened. We had marches and we were trying to fight for our freedom but it didn’t work out and terrible repression started. We were living in the situation where people were just detained from their homes to jail and I was a protest artist. I created a lot of protest works and I just started to fear for my freedom. After my last exhibition in Minsk I understood it’s time to leave. Me and my husband left everything we had, we did not have a job here in Poland, we just came to a place we don’t know. But it turned out to be very beautiful, comfortable and very open to us.

Your parents are still in Belarus.

Yeah, my parents are still there, they are living in the countryside. They have a small cottage house, flower garden, chickens and their own vegetables growing. That was my place of power. I used to spend three months every summer there. And now I can’t go back. I really miss the possibility of hugging my parents whenever I want to.

How was it for you to be an artist in your country?

It was really hard, very hard. My works are in the first place about how I communicate with the world and how I understand the world. So, all of my paintings helped me better understand me and what the world is about. And in Belarus you live in a dictatorship, so you are always scared to say something wrong, to express yourself. In 2020 I believed we are going to be free and it didn’t really happen and I saw so much pain for other people, for my loved ones, for my friends and my art started to reflect that pain, to help me get over the trauma. I guess being an artist in Belarus is feeling too much, feeling more that I can bear. My art helps me, I find the language to understand this trauma. Right now there are black lists of artists in Belarus where all of these artists have no possibility to show their art ever again at any place.

Has anything changed in your work since you came to Poland?

The colours changed completely, when i was in Belarus for the last two years i had a lot of black and red, a lot of these painful colours. When I came here for no reason, light blue, pink started to appear, all of those free colours. It was as if I started to feel more and as if I let myself to feel more. Works i created here are more vibrant, more brighter. I guess that in Belarus I was in a shell and I was very numb. I was numbed by the pain that was happening around me. And here I am now starting to get out of the shell and I am feeling the world much wider. This wideness is coming through my works. When I came to Gdańsk I was wearing a red scarf with a yellow lion. When I got into the bus, I saw red seats with yellow lions. And i thought: Oh my god, this must be something very, very important. And after that I came across that Gdańsk has a symbol of a lion and this lion just mesmerized me. And now I have a lot of lions in my works. Blue lions because they are soaked in all of the tears I had. But those lions are smiling. I’m looking at their faces and understanding that everything is gonna be ok now because I’m here and the lion is kind of protecting me.

Tell me something more about your exhibition which will take place in Krakow.

That exhibition is very important to me. It kind of soaked in these two years of experience of living in a new reality which started in August 2020. All of this new reality, the unbearable, emotional state that people are forced now to live in are lighting up the communication with one another. In this exhibition I’m trying to understand how one and other communicate, how to get out of the violence, how is it possible to kill another person, to be violent toward it.

All of the works are a piece of reflection of our reality. On different levels. I’m trying to find a language to communicate with the new world. It’s also very close to the conception of „I” and „the other” by Emmanuel Levinas, a French philosopher that lived through Holocaust. And he just tries to understand how to live in a world when Holocaust happened, how to live in teh world where evil exists. So, he creates a philosophical system where you have to praise the others on a very high moral high ground in order to always secure the others freedom. That system is what I feel is very important in my life. All of the creations in the exhibition are trying to explore this not possibility of killing another. And the answer from the works that I found for myself is that evil exists, war is going on right now, people are being killed and there is nothing you can do to stop it but you need to do anything to stop it. Spring is blooming, the sun is shining and people are dying. And you have to do anything you can to make the world a better place, to make a change. There is something worth living. That’s something is life itself. Love itself.

What do you feel when you finish a painting?

I feel enlightened. As if I have understood a little bit more about the world I live in. And I feel safe. This is what gives my life and myself meaning.